Director Michael Greif Digs Into His Broadway Hat Trick With Days of Wine and Roses, The Notebook and Hell's Kitchen

(Photo by Jenny Anderson for Broadway.com)

Opening one new musical on Broadway is an enviable accomplishment for any director. But three? In the same season? Michael Greif began 2024 with the Broadway transfer of Days of Wine and Roses, followed by The Notebook (in collaboration with co-director Schele Williams) and Hell’s Kitchen, featuring the music of Alicia Keys. This trifecta of very different shows offered the kind of challenges Greif has embraced since bursting onto the Broadway scene in 1996 with Rent. His musicals have twice won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama (Rent and Next to Normal) and earned Greif four Best Director Tony nominations (Rent, Next to Normal, Grey Gardens and Dear Evan Hansen). During a break from tech rehearsals of Hell’s Kitchen, Greif discussed his current juggling act and his enduring love of shepherding new musicals.

You’re entering the homestretch of your marathon Broadway season. How are you feeling?

That’s very apt: I’m on the homestretch, and it’s a great feeling. I’m very, very happy about how Days of Wine and Roses found its way to Broadway, and how The Notebook is enjoying extraordinary love from its audiences. And now I’m looking forward to putting Hell’s Kitchen in front of audiences to see what we learn. A lot of careful scheduling made it possible for me to be mostly in one place at a time, and I had total trust in Schele Williams as my co-director of The Notebook. It’s actually been invigorating rather than exhausting.

What’s your favorite part of the process of opening a show on Broadway?

There’s a moment of illumination that happens when you put a show in front of a Broadway audience for the first time. These people had to work a little to get there—our show means something to them—and so their responses reveal an incredible amount about what we’ve done right, what we still need to work on and what needs to land better. They’re the final component; we get to sit back and see it through the audience’s refreshed eyes. That’s always my favorite part.

What makes you say “yes” to a musical?

I’m looking for interesting subject matter, interestingly told. Obviously, in the case of Days of Wine and Roses, we’re moving into dark, intimate material. But I’m also proud of the way The Notebook deals with loss of memory, and I’m excited about how Hell’s Kitchen takes on issues of race, what it means to be a mixed kid and what it means to be a single mom trying to give her kid the best that New York City has to offer. I also respond to what the composer and the writer have done. I was dazzled by how Adam [Guettel] and Craig [Lucas] chose to interpret the material in Days of Wine and Roses, and the more time I spend with Ingrid Michaelson and Bekah Brunstetter, the more personal The Notebook feels. With Alicia Keys, of course, it’s that direct line of “I’ve lived through this, and I’m going to give you and [book writer] Kris Diaz the opportunity to re-interpret the seminal moments in my life.”

Given the unsparing depiction of alcoholism in Days of Wine and Roses, what made you confident that Broadway audiences would be receptive to it?

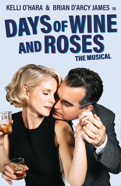

It’s a dazzling work of art that deserves to be shared on the greatest possible scale. I wanted those performances by Kelli O’Hara and Brian d’Arcy James to be shared with the most people possible. I wanted people to hear Adam’s music and lyrics and live in Craig’s beautiful, subtle book. The opportunity to put what we did [off-Broadway] in front of larger audiences was thrilling.

(Photos: Joan Marcus; Julieta Cervantes; Joan Marcus)

And you’ve never been reluctant to bring darker shows like Next to Normal and Dear Evan Hansen to Broadway.

I’m attracted to stories that challenge Broadway audiences, and many times, I’ve found that there is nothing to be fearful of. Certainly, you need to find people who will want to see the show, but there are audiences out there who love the way a musical can open you up emotionally and take you into difficult waters, not just frothy and enjoyable ones. The musicals you mentioned also have exhilarating highs, as does Days of Wine and Roses.

The Notebook seems to be an outlier on your resume, given its very commercial source material.

Here’s what happened: [Producers] Kevin McCollum and Kurt Deutsch gave me the opportunity to look at what Ingrid had written, and I immediately thought, wow, she has really put her own stamp on this. I responded strongly and immediately to the focus on the older couple and their struggles with dementia because that was happening in my life personally at the time with my mom. It was easy to be attracted to The Notebook in spite of its potential for commercial success. [laughs]

"I’m attracted to stories that challenge Broadway audiences, and many times, I’ve found that there is nothing to be fearful of."

–Michael Greif

It's unusual to see “co-directors” credited on a Broadway musical. How did your collaboration with Schele Williams work?

Schele was the associate choreographer on a number of touring productions of Rent, so we have a longstanding working relationship and a very deep friendship. When Ingrid and Bekah and I agreed we wanted a diverse company, we thought it would be a great opportunity to expand our creative team at the highest level, and to make sure that a woman of color could contribute her point of view. The fact that Schele is so good at what she does made it work. She and I found that we could share and overlap and exchange roles very fluidly.

Turning to Hell’s Kitchen, Alicia Keys has made no secret that she is maintaining a lot of control over the show, which could be problematic for a director.

I think it would be problematic if she really was controlling everything, but Alicia is a great collaborator. She certainly has points of view, and she cares deeply about everything that happens in the musical, but she is also generous and interested in what Kris Diaz and I have to say, what [choreographer] Camille Brown has to say, and what the designers are contributing. It’s a wonderful duality because she’s leading the process, but she is also a student of the process. She hasn’t made a musical before, so she brings her extraordinary skills, but also a desire to learn from the rest of us, including our incredible cast.

(Photo: Joan Marcus)

You’ve never directed a jukebox musical. What intrigued you about working with Alicia’s song catalog?

Alicia and Kris never had in mind a “here’s-how-Alicia-became-a-recording-artist” story. It’s a story about a kid trying to find herself, and that idea seemed juicy and dramatic and engaging to me. We agreed that the first song in the musical would not be the most recognizable, and the second and third are original songs written for the show. I’m hoping audiences meet this not as a jukebox musical but as a show in which the ideas and expressions flow completely out of the situation and the characters. Later, as we move into some of the greatest hits, you get that dual moment of experiencing a song in its dramatic situation while remembering the emotional connection you already had with the song.

How would you say your strengths as a director have evolved since Rent?

I sometimes feel like my best work was the earliest work. [laughs] Probably it’s a feeling of security now, of capability, that allows me to hear other perspectives, [including] the audience’s point of view. I’m not out there trying to prove myself, so I can just try to make the most vital and impassioned stories possible. I do feel like I’ve been part of a group of artists who have pushed the musical form, who have opened up the subject matter for what great musicals can be.

With two Pulitzer Prizes to show for it—a rarity for musicals!

Yes, I’m very proud of the fact that there have been a lot of awards for the material I’ve helped develop.

Do you care about winning a Best Director Tony?

I’d like to win a Tony, but if I don’t win one, I’m OK.

If your shows are nominated for Best Musical, which will you root for?

All three, of course. [laughs] I’m going to be OK with a whole lot of different outcomes.

Related Shows

The Notebook

Show Closed

Days of Wine and Roses

Show Closed